An interview with Kathryn Gauci, author of ‘The Embroiderer’

- On 22 Apr 2018

- In Blog

- By Annette

- 2 Comments

We at Odyssey love good books about Greece. On today’s blog we interview Kathryn Gauci, the English author of the wonderful book The Embroiderer. Before she became a full-time writer, Kathryn ran her own textile design studio in Melbourne. We talk about her historical novel, the culinary side of Greece and Turkey and the relationship between the 2 countries.

Kathryn Gauci

The Embroiderer

The Embroiderer takes you through several important moments in history, described with such precise detail that you feel you were there. It intertwines one of the bloodiest massacres of the Greek War of Independence on the island of Chios (1822), the time in Constantinople around the Balkan Wars (1912-13), the Smyrna Catastrophe in Asia Minor (1922-23) and finally WW II (1939-45). Throughout the book, the relationship between Greece and Turkey is a central theme.

The story is told through 3 generations of brave woman (Dimitra, Sophia and Nina) who you cannot help but love, because of the heartbreak they endure during these harsh times in history. It begins in 1972, when Sophia’s grand-daughter Eleni is called from London to Athens by her dying aunt, and discovers the shocking past of her ancestors: a past full of political intrigue, secret societies and espionage. The dominant passion in the lives of these 3 women was embroidery, which all began with Dimitra’s work for the elite of the Ottoman society.

Smyrna Catastrophe

After WW I, the Ottoman Empire collapsed. The Greek Army occupied Smyrna in 1919 with the aim of taking back the land they believed rightfully belonged to them before 1453. Led by Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk), the Turks retaliated. After the Great Fire of Smyrna in September 1922 when most of the city was razed to the ground, and the population exchange six months later, more than 11/2 million Greeks fled to Greece. It was a disaster beyond belief.

You have called Greece your spiritual home. Can you explain why?

I worked in Athens for 6 years (1972-78) as a carpet designer and they were some of the happiest and most interesting years of my life. I was the only English person in the factory and so I was thrown into Greek life from the beginning. I loved everything about the country; the culture, history, music, food, and of course the people, some of whom I still consider amongst my closest friends, even today.

A big motivation for writing The Embroiderer seems to be the opportunity to tell the stories of the refugees of Asia Minor and their descendants. Why did you feel this need?

The carpet factory where I worked, Anatolia, was situated in the refugee area of Nea Ionia / Kalogreza. Almost all the people there were from families who had lived in Asia Minor. At that time, 50 years after the great fire of Smyrna, there were still people who had actually experienced The Great Catastrophe and quite a few who spoke Turkish as their first language.

Even though the factory produced machine-made carpets, there were many who still had hand looms in their homes and either wove carpets on the upright looms or fabric on weaving looms. I bought an upright loom from one of the families along with the weaving implements and learnt to weave the hand-knotted carpets at home. We dyed the wool. I still have a couple even now, knotted with the Turkish knot. None of these skills would have been there had it not been for the Asia Minor refugees.

Carpet design Kathryn Gauci

The relationship and history between Greece and Turkey is a theme that keeps coming back in your work. Why is that?

Because of the strong association I had with the refugees, I identified with their plight and nostalgia for the ‘old land’. As a designer, I love the Turkish culture, especially the Ottoman period. I later travelled to Turkey on several occasions and could understand the connection between the two countries. The bond and their shared history have given so much to each other, despite the struggles and animosities that have taken place.

Turkey is a diverse land geographically, and extraordinarily beautiful in parts and I can well-understand why the Asia Minor Greeks still feel that nostalgia. I might add that I believe that the Muslims in Turkey who were also part of the exchange of 1923, and their descendants, also have the same feeling for Greece, which all goes to show that you just can’t uproot people and expect them to forget about it.

The Greek version of The Embroiderer : The Embroiderer of Smyrna

You have told that your glory years were working and living in Greece. What was it like to live and work in Athens in the seventies?

It was very different. For a start, I was there during the Dictatorship and we lived not far from the Politechnion, so I saw those protests from the start. Every time we passed there would be music by Mikis Theodorakis or Maria Farantouri blaring out. Defiance was everywhere. When the Colonels were booted out and democracy was restored there was a sense of optimism, which started to diminish after Greece’s entry into the Euro zone.

For the wealthy, things went well, but for the workers, prices started to rise and jobs disappeared and then the recession and crisis came. Now things are worse. Things were also different in other ways. I didn’t have a TV and we all socialized a lot more. Music like rebetica made a comeback along with popular music, tavernas were filled to capacity, food was often cooked in the local baker’s ovens which I also used. And there were far more peddlers. There isn’t the variety that there used to be. I miss that street life.

And I lament the passing of such institutions in food as the Milk Cafes who only sold dairy products: eggs, yoghurt, cheese, etc. There used to be a wonderful one in Omonoia Square with marble-topped tables and large mirrors. We used to call in for fried eggs in olive oil after shopping at the fish and meat market in Athinas St. And the basement koutouki’s which sold the best barrelled retsina and mezedes. It’s hard to find those now.

What is your favourite Greek recipe and why?

Garides Yiouvetsi because it reminds me of the first time I ate it in a wonderful taverna in the tiny port of Pasalimani near Piraeus. Both the dish and Pasalimani are featured in my latest novella, Seraphina’s Song.

You have said: design and food will be in every book I write. Why is that and what does the Greek and Turkish kitchen mean to you?

Design is my background. Everything I do and see is through these eyes and I try to bring it out in my novels: the fashions, the food with their tantalising aromas of cinnamon or mastic, the fragrance of jasmine, gardenias, pine resin and wild herbs, the pungent smell of incense inside a basilica. Greece and Turkey may have had a violent past, but there is a sensual side too.

How in your opinion have the Greek and Turkish kitchen influenced each other?

Both have borrowed from each other. Because the Ottoman Empire spanned a huge area, this has resulted in a fusion that has helped to make the cuisine an integral part of the culture. Because the fashion emanated from the Sultan’s Palace downwards, the Ottomans added sophistication and creativity to the cuisine.

The Topkapi kitchen had the finest cooks in the empire producing a diverse array of highly skilled and creative recipes taking Ottoman food to a high art form and many of the elaborate milk-based sauces were created here. Even many of the names are similar. Garides Yiouvetsi for instance is called Karides Güveç in Turkish.

Baklava at Odyssey

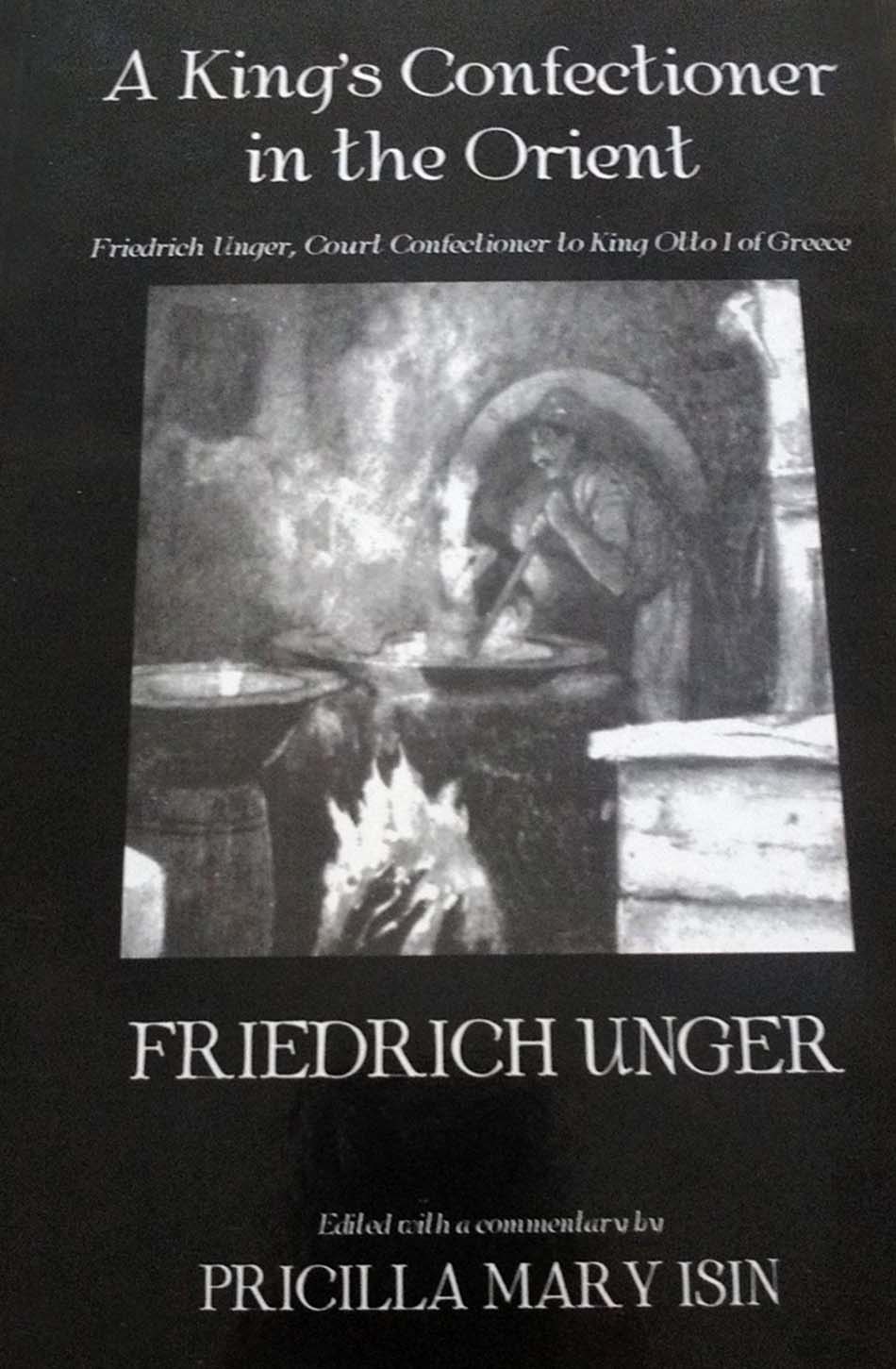

On your blog you write about a very special culinary book you have found: A King’s Confectioner in the Orient. Can you explain what it’s about and why you like it so much?

It is a rare book written by Friedrich Unger, confectioner to King Otto I of Greece, in 1837. He states that it took 5 years to research and it provides us with an amazing insight into, not only the confectionary of the time, but the relationship between Greece and the Ottoman Empire. The book remained unnoticed in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich until it was brought to the attention of culinary researchers by Feyzi Halici, who presented a paper about it in Konya in 1982.

Unger laments the state of confectionery in Greece at that time and pleading ill health, was allowed to travel and study in Constantinople. His book contains 97 authentic recipes, including fruit preserves, sherbets, helvas, toffee-like sweets, Turkish Delights and sweet pastries. Some of the ingredients are intriguing: Musk and opium for example. It is well illustrated and also tells us about the various guilds and sellers. Even Haci Bekir, Turkey’s most famous confectioner, is mentioned. Apparently he was “extremely secretive” about his recipes.

Reading The Embroiderer you get a feel of the elegant and sometimes even sensual etiquette of the Turkish elite of Constantinople. Also when it comes to food. On your blog you write about their tradition of ‘perfuming the house and guests’, like perfuming the teacups before serving tea. Can you tell us a bit more about all of this?

This was a form of etiquette and was carried out throughout the Middle East and parts of Africa too, especially for guests. I experienced it when I was in Khartoum. It does not apply to serving coffee as that involves rituals of its own and would ruin the fragrance and taste.

I’m not sure how this sort of thing came about, most likely through a combination of having access to unusual spices and fragrances because of the spice trade routes, and for hiding unwelcome odours. In Khartoum this was certainly the case. Tiny seeds which were bought in the local market were used to smoke the tea cups. I had no idea what these seeds were but it definitely hid the awful smell of open sewage which was amplified in the heat.

Your latest book Seraphina’s Song is also related to Smyrna and The Great Catastrophe. Can you tell us what the book is about?

It is set in Piraeus in the 1920’s and 30’s, and is a haunting and compelling story of hope and despair. Dionysos Mavroulis is a man without a future: a man who embraces destiny and risks everything for love. A refugee from Asia Minor, he escapes Smyrna in 1922 disguised as an old woman. Alienated and plagued by feelings of remorse, he spirals into poverty and seeks solace in the hashish dens around Piraeus.

Hitting rock bottom, he meets Aleko, an accomplished bouzouki player. Recognising in the impoverished refugee a rare musical talent, Aleko offers to teach him the bouzouki. Dionysos hope for the future is further fuelled when he meets Seraphina – the singer with the voice of a nightingale – at Papazoglou’s Taverna. From the moment he lays eyes on her, his fate is sealed.

All books are sold by online-retailers like Amazon. The Embroiderer is also for sale in Greek in Greece bookstores. Conspiracy of Lies and Seraphina’s Song will also be translated into Greek.

Do you want to cook with Katerina at Odyssey?

Click here for more information!

Leave us your comment

Katerina's Kouzina Blog Post

Thanks for posting this! It’s so very interesting to hear from the author about her life experiences.

I read The Embroiderer about 2 years ago at the recommendation of my dear friend Pamela who lives on Poros. I had not considered it for my book club because I felt my love of Greece & fascination with Greek & Turkish culture might make me an over-zealous promoter of the book. But now I think I will recommend it!

Hi Betty,

I am glad you enjoyed The Embroiderer. The story is a timeless one really. We never seem to learn. Although I wrote ot from a Greek perspective, I never took sides. Both sides were affected. Warm regards, Kathryn